This Monday, Invisible Children released its newest film – the thirty minute Kony 2012. I’ve been involved with IC since early 2007, and my relationship with them is almost always in flux – ranging from being inspired and truly believing in the work to being a critic of the trendy oversimplification. After helping Resolve and the Enough Project gain support for the LRA Disarmament and Northern Uganda Recovery Act in 2010, IC has embarked on a new mission of trying to effectively end the war in 2012, with this video as a part of the broader campaign. The video is centered on Jason Russell, one of the founders of Invisible Children, explaining Joseph Kony, the war criminal in charge of the LRA, to his son. The take-away from the video is that the goal of the next two months is to teach people who Kony is, thus leading to more change and ultimately his capture.

Through most of Monday evening Facebook and Twitter were slowly ramping up in my world. I have met scores of people in my work on the issue, and many of my friends are on the staff at IC, so the hubbub was expected. By Tuesday afternoon, some staff members were tweeting that, in the first 24 hours, the video had been viewed 800,000 times. Late Tuesday evening, the campaign took up six of the top ten trending topics on Twitter, and “Kony” and “#KONY2012” accounted for 3-4% of all tweets.

The last 24 hours (checked at 7:45am, MST today) of Twitter traffic, from trendistic.

Like many who are aware of the crisis in central-east Africa, I would love to see Joseph Kony brought to justice as soon as possible. Kony is the leader of a highly centralized rebel group comprised of abducted fighters – some of them children. Kony is among the first criminals indicted by the International Criminal Court, and his arrest would go a long ways towards ending the Lord’s Resistance Army as we know it and reinforcing an essential international institution like the Court.

”] As I mentioned, I’ve been a supporter of varying tenacity, and I have disagreed with Invisible Children here and there over the years. I support many of their programs on the ground in the region – granting scholarships for students to attend rebuild schools, teaching displaced people employment skills, and building a radio warning system among them – and am one of the many that first got involved in human rights and activism through their work here in the States. I’ve always felt that there is a huge disconnect between the great work being done in the region and the simplistic, sexy, and purely PR work Stateside, which is a shame. I’m not as much of a critic as others, but I do have a few qualms with the current campaign that’s launching right now.

As I mentioned, I’ve been a supporter of varying tenacity, and I have disagreed with Invisible Children here and there over the years. I support many of their programs on the ground in the region – granting scholarships for students to attend rebuild schools, teaching displaced people employment skills, and building a radio warning system among them – and am one of the many that first got involved in human rights and activism through their work here in the States. I’ve always felt that there is a huge disconnect between the great work being done in the region and the simplistic, sexy, and purely PR work Stateside, which is a shame. I’m not as much of a critic as others, but I do have a few qualms with the current campaign that’s launching right now.

Invisible Children continues to oversimplify the message of how to get rid of Kony. I understand that advocacy groups need to take really complex problems and boil them down so that it can be disseminated among supporters. As the movement grows, however, the leaders should be better educating their followers. Being involved for five years, I have yet to see IC expand on its very simplistic history of the war, which is critical to understanding how best to approach ending it.

Something needs to be said about the narrative that IC creates, but I’ll leave that to everyone else. IC has been running programs in northern Uganda for several years – ineptly at first but more recently they operate like any other aid organization there. Meanwhile, their PR campaigns in the States aim to address the LRA, who left Uganda – which has been in relative peace and experiencing slow recovery – in 2006. The videos blur the lines between the countries, and simplify everything to Kony roaming Africa abducting kids. That’s not to mention that there is no evidence of the 30,000 children figure endlessly repeated by IC and other NGOs, and no discussion of how to define abduction (which is important, since some are forced to help transport supplies before being set free, while others are forced to kill their own family members before being conscripted for life). The story IC creates will drive policy, and it needs to ensure that we have a dialog about the peace-justice debate, the accountability of the Ugandan military, and ways to move forwards without losing momentum.

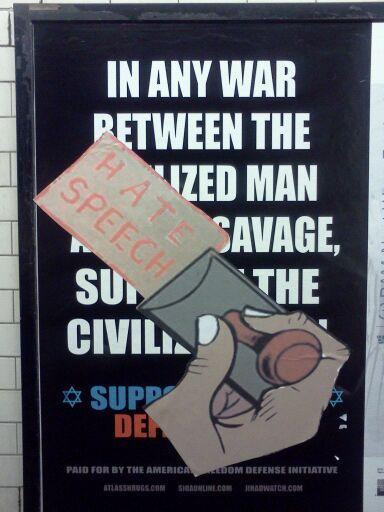

IC’s campaign for the next two months is heavy on awareness. We supporters are to tell all of our friends and put posters everywhere, and then write messages to 20 cultural leaders (who control public discourse) and 12 political leaders (who are involved with real change). This build up is to April 20th, when we’re supposed to plaster our cities in Kony 2012 posters to “make him famous.” There is footage of “Kony 2012” – to make him as popular as possible – a sort of Public Enemy #1.

When I first got involved with IC, I attended an event that included learning about displacement camps in northern Uganda – an eye-opening experience that really pushed me to start a student organization in college. This year’s big event is to put up posters. This is all in the name of garnering more name recognition for Kony to make him (in)famous, but when you get the most bipartisan congressional support for any Africa-related bill in history and you claim hundreds of thousands of youth support you, you’ve gotten the word out. Claiming that nobody knows about Kony (the video says “99% of people” have never heard of him), is absurd. There is enough attention that we can move from awareness to action now. It’s time to pursue real change – front and center. E-mailing the Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee should not just be a side-note to hanging up flags and tweeting at Oprah, who is probably sick of IC distracting her from her work in South Africa anyways.

As Daniel Solomon notes (and you should definitely read his post), if people are tweeting at me to watch the video and aren’t reading the ICG report to learn more, then a vital part of the campaign has missed the mark. Mark Kersten also calls out the campaign in a post you should read, and here’s a critique of “crowd-sourced intervention.”

After six years of building a massive youth-led base in America – including raising millions of dollars in record time and directing masses of young people – we have passed the deadline for moving forwards. In the film, IC tells us the Kony 2012 campaign expires at the end of the year – a movement has an expiration date alright, and it’s important to freshen up the whole IC movement.

Update: The list of related links has moved to a new post, as it continues to grow.