It’s the weekend, you know what that means:

- Party Politics, the Post Office, and the Common Good.

- Elections Matter, on reproductive rights and voting.

- Abortion Care is a Calling.

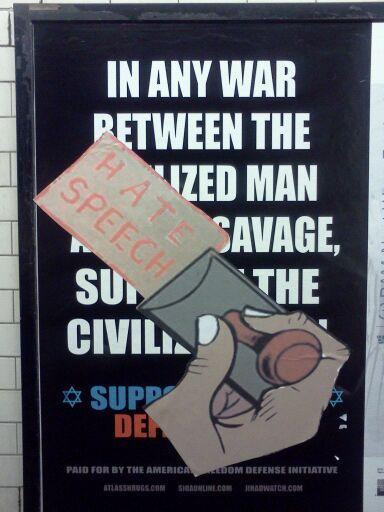

- Eikonoklastes, on the imaginary line between speech and violence.

- The Presumption of Literacy.

- Ralph Nader and the Structure of Progressive Change:

Progressives seem to almost NEVER talk about localized politics. We complain about education reform but don’t organize to take over school boards. Conservatives outflank us in part because they seem to understand that the presidency is not all-powerful. Perhaps local offices like county clerk and elected judges are as or even more important than the presidency, at least from a long-term perspective. Too many progressives believe in Green Lantern presidencies. Elect Obama in ’08 and he can force through all the changes we want.

No. That’s not how it works.

You turn the Democratic Party into what you want it to be by controlling the mechanisms of everyday party life. By becoming a force that must be reckoned with or at least co-opted. By becoming the Populists in the 1880s and 1890s, eventually forcing the Democratic Party off its Cleveland-era support of plutocracy and helping usher in the Progressive Era. By becoming the abolitionists in the 1850s and 1860s, whose constant moral harping gave them power within the Republican Party far outstripping the small number of fanatical followers of William Lloyd Garrison. And by becoming conservatives in the 1960s who burrow into the Republican Party structure and transform it from within.

- How to Change Academic Publishing.

- Letter to the Dismal Center.

- Death Race 2012.

- Why the Blown Call on Monday Night Football Matters.

- The Failure of Muslim Rage.

- Weddings Without the Bride and Groom.

- The War on Crime as a Conservative and Progressive Assault on Liberal Philosophy.

- Are Student Loans Immoral?

Taking out hefty student loans has become a normalized feature of college life. No doubt, this smooth routinization helps to ease the guilt of the admissions officers who are paid to reassure recruits that high-interest loans are still a solid investment in their futures. Those with less conscience have been caught colluding directly with lenders. Parents, for the most part, don’t ask too many questions. They are cowed by the prestige of colleges or are anxious not to puncture their children’s aspirations. As for the borrowers themselves, most are not old enough to drink when they are approached, like subprime-mortgage dupes, with offers they cannot refuse.

Equally problematic are the terms of the loans themselves. Unlike almost every other kind of debt, student loans are nondischargeable through bankruptcy, and collection agencies are granted extraordinary powers to extract payments, including the right to garnish wages, tax returns, and Social Security. The market in securitized loans known as SLABS (Student Loans Asset-Backed Securities) accounts for more than a quarter of the aggregate $1 trillion student debt. As with the subprime racket, SLABS are often bundled with other kinds of loans and traded on secondary markets. With all the power on the side of creditors and investors, it is no surprise that student lending is among the most lucrative sectors of the financial industry. As for federal loans, they are offered at unjustifiably high interest rates—far above those at which the government borrows money.

- American Saints.

- A Black Jack, on Last Resort.

- Socializing in America.

- An attempt at learning about a murdered family member.

- Romney’s “Them” Problem.

- Is the Marginal Cost of a Drone Strike Too Low?

- What Its Like to Be Hit by a Drone.

- Mogadishu: A City in Healing After Two Decades of War.

- Prospects of a Keynesian Utopia.

- Questions About Transitional Justice and the Arab Spring, Part I and Part II.